Remembering Don

It comforts me somewhat to know that I am not alone in my sorrow. Like all great mentors, Don has many mentates, a word adapted from Kurt Vonnegut and science fiction to better describe the disciplineship involved in having a mentor.

I first met Don when he was head of the Janeway Hospital in St. John’s charged with establishing pediatric training in Newfoundland’s first medical school. He had come to the Janeway from Montreal with his wife, Liz, also a pediatrician. This wasn’t the first time they had undertaken such a challenge. With their five young children in tow, they had gone off to Nairobi for McGill University to help establish pediatric specialty training in Kenya ten years earlier.

I first met Don when he was head of the Janeway Hospital in St. John’s charged with establishing pediatric training in Newfoundland’s first medical school. He had come to the Janeway from Montreal with his wife, Liz, also a pediatrician. This wasn’t the first time they had undertaken such a challenge. With their five young children in tow, they had gone off to Nairobi for McGill University to help establish pediatric specialty training in Kenya ten years earlier.At the time we met, I was the travelling doctor of the northern Labrador coast for Grenfell Health Services. Residing in the Inuit hamlet of Nain, the most northern settled community on the coast, I traveled back and forth from Nain to the other Inuit and Innu settlements staffed with nursing practitioners along the coast, Rigolet, Postville, Hopedale, Davis Inlet and Makkovik. Most of our pediatric referrals went to Goose Bay but occasionally when tertiary care was required a child would be sent to St. John’s, more than 1500 miles to the south.

On one visit to Davis Inlet, a tiny community of 250 Nascaupi normadic hunters still living on the land, the nurses and I resuscitated a dehydrated, convulsing nine month old infant and sent him on the long trip to St. John’s ICU. We called regularly for updates for the parents and ourselves. Then one day two Mounties (RCMP) in full uniform flew into the tiny hamlet to arrest the parents for child abuse. Luckily, as this was a rather unusual task at that time, they first dropped by the nursing station where the nurse recognized an enormous mistake had been made. The parents were well known to us, and not abusing the child.

The Mounties were sympathetic. They said they had other things that needed to be done on this visit to the coast, but while they could delay a little they could not ignore the instruction. Their order had come directly from the Department of Justice and even their bosses were unable to withdrawn it. This was something you will understand, that took a number of phone calls to ascertain.

We were frantic and not sure what to do. We were unable to find out who was on the Child Abuse team and calls to the doctors, ward and ICU failed to produce anything useful. Finally I contacted the head of the Janeway. By this time I was under a full head of steam. Dr. Hillman heard me out and asked a few pertinent questions. He seemed to appreciate what a miscarriage of justice this would be and how devastating in this small community. Then he asked, “What can I do?". I was so taken aback, I was, for a short minute, speechless. I had been hearing so many versions of, “It really isn’t my problem”, or “I think it is too late” that I was totally unprepared for someone who cared.

“ Well,” I said, much bolder than I actually felt, thinking we might as well go for bust, ” we need someone to phone the Minister of Justice and withdraw this order”.

“Done”, said Don, “anything else?”

Obviously a busy man, I thought, so better get it all in now.

“Well, that Child Abuse team needs an overhaul.” I said. “They didn’t even contact us and our numbers and names are in the kid’s chart. “

“That might take a bit longer,” he said, “but I agree.”

Don was like that, decisive and willing to take responsibility. He was also a master at sorting the fluff from the seeds, seeing through the histrionics to the wound. He had time to listen to an inarticulate cry from the wilderness and to really get the full impact of the story behind it. This combination was decidedly unusual in tertiary care centers, which, at that time, had a remarkable lack of interest in their more remote service areas. He had done the right thing and I was grateful. I didn’t give it much further thought.

A couple of months later, I needed a supervisor for my community medicine residency. It had to be someone in Newfoundland with a fellowship. My main supervisor suggested Liz Hillman, whom he had met at the Medical Council. Liz willingly agreed and a six week spell in St. John’s was organized in ambulatory pediatrics for me. No mention was made of the Mountie Episode, as I came to call it. I assumed Don had not made the connection that I was the irrate doctor on the coast.

Don had a way of taking in much more than any narrow view of his specialty or corner of the world would dictate. It wasn’t long before he decided since there was no community medicine grand rounds for me that I ought to come to his Pediatric rounds, to get in some critical thinking. He was a pediatric endocrinologist and really grilled his residents, but he made an effort to direct my way challenging community questions that added to the rounds and also sent me scurrying to the books. He challenged all of us to provide solid evidence and to support our points. He wanted us to see the whole picture and the connections. It was no surprise to me to find his residents scored near the top, even though the program was a new one.

Don’s greatest success was not however in pediatric endocrinology, despite his academic excellence, but in international health. With Liz, he created a world wide linkage of medical education projects and people over the years. In his so-called retirement he continued to lead problem based learning workshops for students in Ottawa and McMaster and built up the international health program in Ottawa. He was working with Liz on a project to document some of the medical education successes in East Africa for the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada when he died.

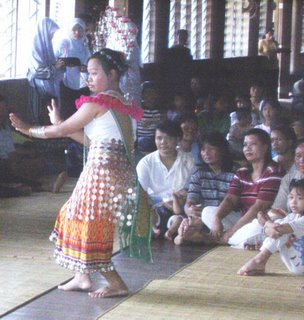

I did one of those mapping exercises of my connections and jobs in international health and found that almost all of them link in one way or other back to Liz and Don. Others too have been influenced greatly by them over the years. One of the first online guest books I have seen is attached to Don’s obituary. It has attracted comments from Uganda, Kenya, Pakistan, China, Malaysia, US and Canada. The guest book allows those of us who have known and worked with Don to acknowledge our global connectedness and caring, and indeed our common medical origins. This appreciation of our global connectedness in medicine was one of Don's great gifts to us and is surely a much needed antidote for the alienation so many in the world feel today.

A year ago, I needed a dose of Don and Liz's optimism and enthusiasm for global health. We had a chance to link up while they were being entertained as WWII veterans in the Netherlands and I was visiting friends in The Hague. I turned up in the lobby of an overbooked hotel in Appledorn and soon was bedded down in a pullout couch in their room. Don’s army buddy, a retired judge, had kept a diary of all the places they had traversed in Holland during the war, so the following day, a young Dutch family who had adopted Liz and Don, escorted the whole group of us around to the various sites. Don and Liz had this wonderful knack of making friends everywhere they went. And once again, as was so often the case, the whole time I was with them, supposedly on holiday, we were reviewing articles, plotting projects and exchanging connections.

Just last November, when Don was 80, he and Liz joined me in East Africa to teach pediatric residents and students and to provide feedback on student inclusion in a child health project. He and Liz set off for a long bus ride to Gulu in the war-torn north of Uganda with several potential projects in their pocket for an isolated hospital there. Just one month before he died, we received word that a Pakistani project we had prepared at the request of an NGO working in North West Frontier Province had been funded for two years.

I had a dream the other night that he hadn’t really died. I believe my dreams are the real, unvarnished truth, the gold as Marion Woodman says. This dream was so real I woke up thinking I had made a big, Mark Twain type of mistake, as in "the stories of my death have been greatly exaggerated". Then I recognized the gold. One can’t lose a mentor, it is a gift that never ends. I will always have access to him over my shoulder. Just writing up the story of how we met, I can hear him laughing, "Whose version do you want to hear?".

His gift of mentoring will continue to manifest though his wife, Liz. Then, too, its pretty hard to be sad about such a productive, fruitful, wonderful more than 60 years of medical service.

Photos: Don and Liz receive the Order of Canada; Don & Liz at the 60th celebrations of VE day in Holland and Don & Liz in a dugout canoe, Lake Bunyonyi, Uganda.

Labels: Friends