Longhouse Visit near Bintangor

About 50 miles east of Kuching, longhouses begin to appear. Most are located along rivers, some visible from the road. In the forest the longhouses are perched atop long pole stilts high above the rainforest floor. They are an example of linked cooperative housing that has been around for ages. Hand hewn long boats that hold as many as 60 men are collected on the river below the longhouse with paths leading up the bank. The long boats are almost unchanged in appearance from the war boats that established the Sea Dyaks as fierce pirates of the South China Sea. Young Iban men still race them, a wondrous sight of 80 synchronized paddles flashing as they fly across Kuching harbour.

The distinctive feature of a longhouse is the communal area, a long, tall, covered area opposite the doors, that extends the length of the longhouse. The communal area has a floor of hand-sawn, dark, wide planks from the rainforest smoothed and polished by the passage of many feet. I can’t imagine the effort required to do the work by hand. And it has created a floor that actively responds to your barefooted crossing. The ceilings are high and with the many large windows ensure Borneo breezes can move through.

When I first heard students talk about doors, I thought I had misunderstood or that they were talking in Malay and it just sounded like English, or any of the numerous assumptions one makes when confused. This happens fairly frequently here with the constant switching between English, Chinese, Bahasa Malay and Burmese that surrounds me. Finally after it has gone on for a while, as in, "How many doors? Is that all the doors? Are there any doors on the other side", I inquire, “Why are we talking about doors?” This was before I had actually been inside a longhouse. I like to think the penny would have dropped if I had visited a longhouse b

When I first heard students talk about doors, I thought I had misunderstood or that they were talking in Malay and it just sounded like English, or any of the numerous assumptions one makes when confused. This happens fairly frequently here with the constant switching between English, Chinese, Bahasa Malay and Burmese that surrounds me. Finally after it has gone on for a while, as in, "How many doors? Is that all the doors? Are there any doors on the other side", I inquire, “Why are we talking about doors?” This was before I had actually been inside a longhouse. I like to think the penny would have dropped if I had visited a longhouse b efore we had started to design survey questions for people living in one, but that may be wishful thinking. There is a shocked silence as if I have really this time confirmed how ignorant Europeans are, then a gentle, tinkling giggling that swells into rolling-on-the-floor laughter until someone gasps out, "Behind each door is a household” as a translation for me.

efore we had started to design survey questions for people living in one, but that may be wishful thinking. There is a shocked silence as if I have really this time confirmed how ignorant Europeans are, then a gentle, tinkling giggling that swells into rolling-on-the-floor laughter until someone gasps out, "Behind each door is a household” as a translation for me.This longhouse near Bintangor has 114 doors. The walls of the longhouse are panelled in the same dark woods of the rainforest as are the floors. All of the work was done by those who live here with materials drawn from their world. The walls are unadorned so their beauty catches you full force when you first enter. Hilton has built a longhouse Hotel at Batang Ai which most guests reach by helicopter from Kuching. Miraculously, although the communal areas lack the people and easy camaraderie of the Iban porches, the architect has managed to replicate that same powerful sense of the longhouse.

People of course are many in a longhouse, especially little people, with approximately 15% of the population under five. The layout of the longhouse makes it possible to easily care for groups of children and engage them early in the tasks of the longhouse. During the day nets are patched, rattan mats woven, baskets created and cloth woven in the covered communal spaces often surrounded by small children. Parallel to the roofed part of longhouses there is an floor extension made of poles and covered with rattan mats, that is only partly covered. Tasks such as winnowing, drying, sorting and processing crops are done on here on the porch with children underfoot.

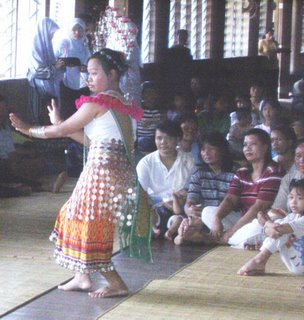

People of course are many in a longhouse, especially little people, with approximately 15% of the population under five. The layout of the longhouse makes it possible to easily care for groups of children and engage them early in the tasks of the longhouse. During the day nets are patched, rattan mats woven, baskets created and cloth woven in the covered communal spaces often surrounded by small children. Parallel to the roofed part of longhouses there is an floor extension made of poles and covered with rattan mats, that is only partly covered. Tasks such as winnowing, drying, sorting and processing crops are done on here on the porch with children underfoot. Today the 4th year students who have been working in this longhouse are having a celebration with some health education thrown in and the longhouse is decked out. This longhouse has two sections facing each other and is set closer to the ground than most. The display is set up in one side while the food and entertainment is on the other side. A decked out longhouse has its pua kumbu displayed. Pua kumbu are the woven art of the Iban, a textile which is well known amongst textile connoisseurs and museums because of the exquisite and intricate patterns created using the warp-ikat technique. Ikat hand woven blankets are the high art of the Iban. At present there are weavers in only a few longhouses but more young women are learning.

Today the 4th year students who have been working in this longhouse are having a celebration with some health education thrown in and the longhouse is decked out. This longhouse has two sections facing each other and is set closer to the ground than most. The display is set up in one side while the food and entertainment is on the other side. A decked out longhouse has its pua kumbu displayed. Pua kumbu are the woven art of the Iban, a textile which is well known amongst textile connoisseurs and museums because of the exquisite and intricate patterns created using the warp-ikat technique. Ikat hand woven blankets are the high art of the Iban. At present there are weavers in only a few longhouses but more young women are learning. Pua kumbu are made of two parallel strips of cloth woven on a backstrap loom and then sewn together in the middle. Shorter sections of cloth are used for women’s skirts and made into vests and shirts for the men. This style of ikat is found throughout Southeast Asia in the sophisticated cultures of Laos, Burma, Cambodia and Thailand as well as in China and Japan. The version found in Borneo uses natural dyes of creamy red brown, chocolate brown, black, burnished red and ochre with designs that are not only finely geometric but that depict the animals and events of their lives. Pua kumbu are vibrant with crocodiles, people, spirits and birds as well as the decorative images found els

Pua kumbu are made of two parallel strips of cloth woven on a backstrap loom and then sewn together in the middle. Shorter sections of cloth are used for women’s skirts and made into vests and shirts for the men. This style of ikat is found throughout Southeast Asia in the sophisticated cultures of Laos, Burma, Cambodia and Thailand as well as in China and Japan. The version found in Borneo uses natural dyes of creamy red brown, chocolate brown, black, burnished red and ochre with designs that are not only finely geometric but that depict the animals and events of their lives. Pua kumbu are vibrant with crocodiles, people, spirits and birds as well as the decorative images found els ewhere. It is amazing that such an art survived in Borneo and astounding that it flourished.

ewhere. It is amazing that such an art survived in Borneo and astounding that it flourished.Pua kumbus play an important part in the rituals and culture of the Iban whose oral culture goes back at least 40 generations. The pua kumbu are historical documents that captured spectacular feats, celebrate history and delight the eye. They pulsate with liveliness. The rest of the world is only now discovering pua kumbus. The cost of smaller pieces has increased four or five times over four years, with some of the older finer examples selling for thousands of dollars.

I am absorbed by the beautiful collection of pua kumbus owned by this longhouse. An elder watches me taking close-ups of them all and smiles. He has a gentle, engaging face. I greet him and he suggests through an interpreter that I take pictures of his tattoos, positioning himself so more of them can be seen. There now are few people under 40 years old with tattoos. He is, they inform me, over 80 and the tattoos attest to an active life as a warrior. I wonder where he was during the Japanese occupation of the war and what stories he could tell. I hope there is some program where the young people are collecting the stories of the elders here, but when I inquire, no one seems to know.

The longhouse we are visiting is progressive and has a female chief. We are invited into the living quarters. Behind the doors, the individual homes contain sleeping and cooking spaces. Ancient enamelled Chinese pots hold quantities of rice, stacks of rattan mats lean against the wall, babies are lulled to sleep in swinging hammocks as do the Cree Indians in the north and baskets and knives are suspended from the wall ready for use.

We are treated to an orchestra of brass gongs and women dancing in their filigree silver headdresses with long languid hand movements. It’s a whole new world for me and I am grateful to see it as it is now.

Photos: Longhouse with drying mats outside; longboats tied up on the river side; communal porch; kitchen wall; babe in hammock, pua kumbus, pua kumba with overlay showing how warp threads are tied; elder with tattoos; Iban dancer.

Labels: Sarawak

1 Comments:

fantastic! ill give you a link right now!

Post a Comment

<< Home