Refresher Training

Clotilda comes by at 4pm to tell me there is a two day CORPs (Community Owned Resource Person) Refresher course in Kitunguru, next morning. These refresher courses are held for volunteers two years after they were originally trained. Clotilda has been facilitating community work for the university for years and is one of our most gifted and stalwart trainers. One of the two other trainers took violently ill and has been in hospital for the past week while the other has to to tend to urgent family matters. So Clotilde is not only running out of time but has 4 new trainee trainers to deal with alone in this workshop. Even our project staff are caught off guard and have to scramble to obtain funds at the last minute.

Clotilda comes by at 4pm to tell me there is a two day CORPs (Community Owned Resource Person) Refresher course in Kitunguru, next morning. These refresher courses are held for volunteers two years after they were originally trained. Clotilda has been facilitating community work for the university for years and is one of our most gifted and stalwart trainers. One of the two other trainers took violently ill and has been in hospital for the past week while the other has to to tend to urgent family matters. So Clotilde is not only running out of time but has 4 new trainee trainers to deal with alone in this workshop. Even our project staff are caught off guard and have to scramble to obtain funds at the last minute.

“What things do you need? What can I do to help,” I ask.

"Let me see what there is," says Clotilda.

Everything from the previous workshop has been left in a big bag, unsorted, so I show her to the cupboard.

“What is on the program,” I inquire, hoping to get some clue of what training materials are needed.

“I’m not sure”, she says. “We organized the timetable at the planning workshop three weeks ago.

“I’m not sure”, she says. “We organized the timetable at the planning workshop three weeks ago.

If I didn’t know her better, I would panic. But she is a natural and gifted trainer so I start pulling things out that we have done before or talked about lately. We start a check list and come up with about 8 sessions, starters and some energizers.

We were going to introduce the puppets, so I haul out a bag, count them and add them to the pile. I toss in copies of a handout I prepared for the trainers on how to make puppets more effective.

The Family Planning counseling cards and the board games we want to introduce have not been translated or put on heavy card. More felt characters are needed for the flannel board display on contaminated water. By now, the project staff have joined us and we are all scrambling. I suggest an introduction using a banana fibre ball toss around the circle which Clotilda has done before. We add the Tippy Tap to the training bag. It’s a wonderful gadget the CORPs can introduce to their villages to conserve precious water. We have a couple of pictures that can be used for starters in Malaria and Growth Monitoring if we can just find them. For the session on special children we need blindfolds, ear plugs and long ties to bind arms and legs so participants can experience what it is like to be disabled. We tear up short cloths to use as blindfolds but come up with only 3 pairs of ear plugs. The power is out again so I am unable to download and print the pictures we need or to laminate the ones we have located. It is shaping up to be a trainer’s worst nightmare.

By this time we have found the outline program of what was originally planned. Most of what we have pulled together will fit. We weren’t planning to do Family Planning but we think we probably will include it anyway. The training method we use is a double circle counseling. Half of the group act as clients and half as counselors. Each client with a specific situation hears from 11 different counselors. And then they switch and clients become counselors, counselors become clients. Although each “session” is only 2 minutes, the exercise is very effective in bringing home the necessary components of counseling---listening, asking open questions, rephrasing, not judging, showing interest, addressing people by name and knowing where to refer people for appropriate help. The Family Planning session is thus more about effective listening and carries over into other areas well.

The project secretary goes off to translate the cases into Runyankole. The driver stays up all night translating the board games and drawing the snakes and ladders. At midnight I finish cutting out felt silhouettes of a water pump, a newborn baby, a grave marker and a small child. In the morning the power is back on so I get up early, heat up the laminator and cover some of the pictures and cards we will need.

We drop by the health center before heading into the field. Clotilda shows me the new, brightly painted walls on the ward. I am surprised and gratified that most of them are versions of the pictures in our new training manuals.

We drop by the health center before heading into the field. Clotilda shows me the new, brightly painted walls on the ward. I am surprised and gratified that most of them are versions of the pictures in our new training manuals.

We greet Sarah, a CORP who works as a cleaner at the health center and thank her again. When Joseph, one of our trainers, was taken as an emergency to hospital Sarah offered to stay with him and cook until his family arrived.

Families are often split up here, with one spouse working in one part of the country and the other spouse far away. So getting Joseph’s family here takes a couple of days. In

Organizing Joseph's stay has taken a whole group of us. We contributed food, dishes, sheets, mats, milk, transport and blankets. All of us are grateful to Sarah for dropping everything to take care of Joseph and his son.

Restituta, our project manager, who organized Joseph’s transport to hospital and called his family says, “It’s like we are one big family.”

And indeed it is. It takes a whole extended family to care for you in

On the way to the village site where we will have our training, we stop to collect morning tea. Because there wasn’t time to make the arrangements, tea will be sodas and mandazi, a deep fried type of donut. We catch the morning migration of milk cans being taken on the back of bicycles to the dairy collection site. It is a reminder that we won't be having any milk tea today.

I have printed up a draft timetable in English for the trainers. We have relegated those sessions that need additional preparation to the second day. Two of our trainee trainers have arrived by the time we get there so Clotilda and I fill them in on what needs to be done. They are eager to gain experience and agree to try out some new sessions. Then off we go..

Understandably, there are a fair number of glitches, but the participants don’t seem concerned. The trainee trainers are confident and spirited. There is lots of laughter. There is however, one session when everything comes to a halt as the whole group watches one person in each group laboriously writing down questions. About half of the CORPs are illiterate so reading and writing even in their own language doesn’t come easily. As trainers, we had agreed we would stop using writing on paper as a technique, but somehow this has been forgotten. I feel I must intervene and do. I wish there was a nice way to do it but I haven’t found it.

So I say, “Let’s try it without writing.”

There is silence.

“Well”, I add, “I noticed that the discussion in the group has all stopped. This is supposed to be a group discussion, so I wonder if we could put down the pen and paper and just talk.”

“They are writing down the question,” says the trainee trainer.

“We want to get the questions down”, the group adds.

All of this takes more time because of the need to translate back and forth. Then I take the paper and sit on it.

“Now what are you going to do?” I ask.

Another silence and what seems to be confusion. I am given a lot of deference here and so am expected to behave in a certain way. Sometimes when we show pictures of health practices, people will state that the people were smart and therefore their behaviour is healthy, even if it isn't. So appearances are highly regarded here. By behaving out of character, I have upset the applecart. Even, I reflect later, I may have obscured the message entirely.

“Well, let’s do the questions one at a time, then,” I continue. Finally, the discussion starts.

I might do this at a workshop at home and people would get the point, but such an approach can come across as interference here. I am lucky because the trainers are used to me and they take it well. Later at our debriefing they mention that they are going to cut out the writing completely. I cheer and everyone laughs.

I put these slips in process down to lack of preparation. You really need to walk through your whole session and have everything in order so that you can make it look as if you are winging it. The trainers understand that it is supposed to look seamless but sometimes they are caught out when they haven’t prepared. At least that is what I think happens.

North Americans trainers might have all the content, sequence and materials in order but hardly ever are able to make a session flow the first couple of times. Africans seem to catch the essence right off. Som etimes I am bowled over with what they come up with in roleplays, poems, songs and drama. It all comes together so seamlessly. Then, at times like this, I begin to doubt whether they have understood the whole point of experiental learning and whether they are keeping an eye on what's happening in the groups.

etimes I am bowled over with what they come up with in roleplays, poems, songs and drama. It all comes together so seamlessly. Then, at times like this, I begin to doubt whether they have understood the whole point of experiental learning and whether they are keeping an eye on what's happening in the groups.

Clotilda wants to do a flannel board story about contaminated water. We made up a story after a visit to a remote site where the whole community, including animals, were using a pond for drinking water. The local chairman was sure at least one child was dying every two weeks and half the community had diarrhea.

The story, told with felt cutout figures on a flannel boad, brought the room to stunned silence. For the rest of the day, people referred to the situation and what could be done to improve it. Clotilda wants to do her own version slightly differently, which makes me very proud, so I make the extra pieces she wants. Attention is riveted on her while she tells her story. Afterwards they want us to leave it up, “so they can think about it more.” The flannel board seems to work best when it portrays a real, local situation which the figures reinforce visually. Clotilda’s addition of a sick baby, followed by the grave not only reflects reality here but is dramatic and  brings tears to my eyes.

brings tears to my eyes.

We have been unable to find or purchase flannel board pieces. So I have been cutting and sewing bits of felt together. I am not an artist so I use silhouettes. Some of my trainers wanted to make a malaria story on the flannel board, but were unable to do it despite cutting up a fair amount of felt. Children here do not have a lot of exposure to crafts so those skills seem to be vestigal in many. However it seems simply a matter of exposure because in other parts of Africa it is part of the culture and beautiful applique cloth is created and stamps are carved to use for printing cloth.

I agree to make some figures for malaria but warn them that we can’t always scare people with death and destruction in our health messages. Once again, I may be wrong. Here, health prevention messages often do make the difference between life and death.

I have also been thinking about how nothing ever gets stolen at our workshops. People don’t help themselves to even pens, markers or paper. Yesterday I lost a bag full of four lengths of

So todayI retraced my steps of yesterday and at the stall where I bought the carved Ankole spoons, the trader had my bag intact with the material. She said she knew one of her customers must have left it, just not which one.

It’s a big lesson. I need to trust people more. I’m the klutz who keeps misplacing things. Nobody is out to steal my things. They are doing their best to assist me. Including the trainers at the workshops.

Puppets are one of the interactive ways we are introducing. It has turned out better than I had hoped. Several of the senior and junior trainers are very adept and can already move the mouth in the shape of words. All of the CORPs at our workshops have practiced making health messages with puppets. CORPs who are learning to be trainers and all the senior CORPs being retrained will receive a puppet to use in the community and schools.

Puppets are one of the interactive ways we are introducing. It has turned out better than I had hoped. Several of the senior and junior trainers are very adept and can already move the mouth in the shape of words. All of the CORPs at our workshops have practiced making health messages with puppets. CORPs who are learning to be trainers and all the senior CORPs being retrained will receive a puppet to use in the community and schools.

The CORPs have made up funny voices, great dialogue and dramatic events with brilliant climaxes. They are delighted when they find they can move the legs, arms and mouths of puppets. They are getting used to watching their puppet instead of the other person and to holding the puppet so that it can be seen. We are in for some great puppet shows.

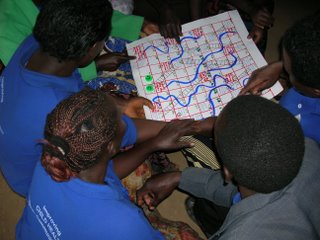

Another teaching approach we have successfully introduced is the making board games with health messages. Our trainers have created snakes and ladder games for malaria, hygiene and immunization in Runyankole. Answering questions correctly can prevent your slip down the snake or let you climb the ladders. The first six games were drawn on the back a large calendar made of firm quality paper. I think it was a

It is said if you teach you need to keep learning from your students otherwise your messages become hackneyed, your work uninspired and you become bored. So I always wondered, if that was true, why the most eminent professors in medical school seem to enjoy teaching the introductory classes or as often happens nowadays facilitating problem based tutorials in fields other than their own specialty. I would hazard a guess, at this point in my career, that it is precisely because working with beginners you can be caught off-guard, can be surprised and can see things from a different perspective. It is with the beginner's mind that we can make quantum leaps in understanding that allow us to drop deep into areas we thought we understood and yet were only up till now, merely skimming the surface. What started out as a slap-dash, last minute workshop has proved to be refreshingly full of insights for me.

is said if you teach you need to keep learning from your students otherwise your messages become hackneyed, your work uninspired and you become bored. So I always wondered, if that was true, why the most eminent professors in medical school seem to enjoy teaching the introductory classes or as often happens nowadays facilitating problem based tutorials in fields other than their own specialty. I would hazard a guess, at this point in my career, that it is precisely because working with beginners you can be caught off-guard, can be surprised and can see things from a different perspective. It is with the beginner's mind that we can make quantum leaps in understanding that allow us to drop deep into areas we thought we understood and yet were only up till now, merely skimming the surface. What started out as a slap-dash, last minute workshop has proved to be refreshingly full of insights for me.

We all go home reinvigorated with a Tippy Tap that we have made by ourselves from a plastic jerry can, some string and a couple of sticks. It is a wonderful device that saves precious water by only letting a small amount out for each person. The Mbarara version of this invention by Canadian Jim Watts, has a foot pedal so you don't touch anything with your hands. Our CORPs, by example, will help to spread it to their communities.

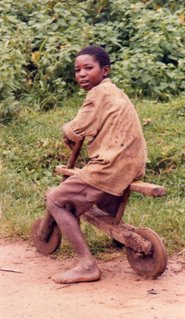

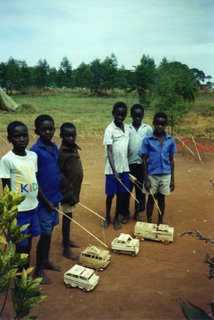

Photos: 3 Card Sort, Using Ball, Painted walls of HC, Milk cans on bicycle, Snakes and Ladders,Flannel Board,Puppets, Puppets, Tippy Taps made from gourds and plastic jerry can

Labels: Uganda