Remains of the Silk Route

It isn’t just that everything seems to be on the move, although that certainly is one impression, as that what is moving - the vehicles, the animals, and the goods shifted from place to place-- is so decorated, diverse and alive. Pakistan seems to be part of an ongoing celebration of travel that probably dates back to the caravans that moved precious cargo along the Silk Route from Arabia to Mongolia.

It isn’t just that everything seems to be on the move, although that certainly is one impression, as that what is moving - the vehicles, the animals, and the goods shifted from place to place-- is so decorated, diverse and alive. Pakistan seems to be part of an ongoing celebration of travel that probably dates back to the caravans that moved precious cargo along the Silk Route from Arabia to Mongolia.Being met at an airport ranks high on my list of favourite things. In an unfamiliar airport, spotting a couple of familiar bearded faces beneath the distinctive rolled woolen brims of Chitrali hats, I am overjoyed. What a welcome sight to the jet-lagged and sleep deprived traveler. With bags stashed safely in the back, the driver wraps the ubiquitous brown wool shawl about him and hunkers down in the van for a couple of hours of shut-eye. Meanwhile, Aazim, the project administrator and I drink milk tea in the all-night cafeteria. An hour or so before dawn, when the situation is judged safe enough for us to be on the road, we set off on the journey from Islamabad to Mardan.

Pakistan is under what the Canadian High Commission refers to as a travel advisory, so it is best to be careful and prudent and my hosts are all of that. I am still in a bubble of euphoria after having secured a visa in time. Just two weeks before I was meant to travel from Uganda to Pakistan, I learned I needed a visa. Getting a visa to Pakistan from a third country is somewhat difficult these days. It took a while to locate the Pakistani consulate five hours away in Kampala. When I went to plead my case, I carried my passport, a letter of reference from a Ugandan physician who has known me for years and an email from the Pakistani NGO regarding plans for the visit. Luckily, the Commissioner knew the physician and undertook to expedite the visa. It felt like touch and go over the next two weeks but I was able reclaim my passport with visa in Kampala the day before my plane for Pakistan left. So just getting here feels like it was meant to be.

The only traffic on the road, the night that I arrive, are lorries. I can barely make out the brightly coloured sides and the beautifully worked wood panels in the dim morning light, but the sight of these brightly coloured lorries makes me instantly feel back at home in Pakistan. Nowhere else do such wonderfully, exquisitely painted and refurbished working lorries exist. What does it say about a country when such effort goes into beautifying their heavy duty transport? Front and back metal pendants and chains swing from their bumpers and undercarriage, tingling and dancing in the draft. Rows of reflectors are strung from the front of one cab while mural-like paintings of tigers, women, flowers and movie stars adorn the large panels at the back.

The three hour trip back is uneventful. Most of our catching up has been done in the cafeteria. Now Aazim sleeps wrapped in his brown shawl. At the first call of the muezzin, we stop again for them to say early morning prayers. An hour or so later, when he feels sleepy, the driver makes a brief stop for some tea.

The next morning as I wait for the van to pick me up, I am taking pictures of men working on the building next door when a young milk seller, peddling by the guest house stops and gestures for me to take his photo. I gladly oblige, thus beginning to document the various modes of transport.

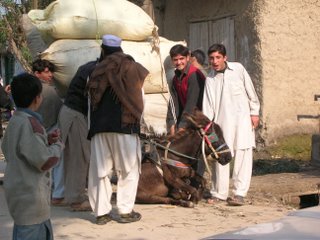

On a trip to a refugee camp clinic, I am trying to get a picture of the kids harvesting sugar cane by the roadside. The accompanying staff admonish us firmly that we are not allowed to stop here. Security is tight right now with advance permission needed for travel of foreigners to the refugee camps. We can travel through the camps to the clinic but cannot stop even briefly enroute. Suddenly we find the narrow road blocked by a group of young Afghani men who are trying to coax a donkey to his feet. The donkey lies collapsed, legs spread out on the ground in front of an overloaded cart. The staff begin laughing and exclaim excitedly, “Now you can take picture! This is good picture.” I am still trying to capture the kids in the sugar cane field so have missed the donkey mishap. The Afghanis are trying to lift the donkey but to no avail. This is what it means to be as stubborn as a donkey!

On a trip to a refugee camp clinic, I am trying to get a picture of the kids harvesting sugar cane by the roadside. The accompanying staff admonish us firmly that we are not allowed to stop here. Security is tight right now with advance permission needed for travel of foreigners to the refugee camps. We can travel through the camps to the clinic but cannot stop even briefly enroute. Suddenly we find the narrow road blocked by a group of young Afghani men who are trying to coax a donkey to his feet. The donkey lies collapsed, legs spread out on the ground in front of an overloaded cart. The staff begin laughing and exclaim excitedly, “Now you can take picture! This is good picture.” I am still trying to capture the kids in the sugar cane field so have missed the donkey mishap. The Afghanis are trying to lift the donkey but to no avail. This is what it means to be as stubborn as a donkey!

A couple of lorries loaded with sugar cane pile up behind us impatiently blowing their horns. It is easy to see why the donkey won’t move. His load is piled so high it seems almost impossible a task. Finally after repeated attempts, the men begin to off load some of the huge sacks from the donkey’s cart so the road can be cleared. This is Pakistan all over. One is not allowed to do something and then events conspire so you are forced to do it. It is not lost on the staff who clearly see the paradox in the situation.

Small donkeys are everywhere, pulling all manner of loads. Most of the animals seem relatively well cared for and many are decorated with tassels and ribbons. When I stop to catch a shot of a donkey with a load of tires on his cart, his owner tells me to wait until he has him piled up higher.

I laugh and tell him, “He is just fine as he is.”

Another man asks, “Why you want picture of donkey?”

“Because he looks so nice”, I respond.

The man takes another look at the donkey in disbelief.

There still are many horse-pulled tongas for moving people around in most cities but in Mardan their role has largely been taken over by the QingQi, (pronounced Ching Chee) a bright yellow motorbike rickshaw imported from China. People say they have only been around for a couple of years. They are very useful but spew out blue smoke and appear to be much less environmentally-friendly than horses but they are certainly popular and cheap. The motorized rickshaws near our guest house seem to specialize in Kung Fu art. The drivers are very pleased to pose when we want to take pictures of them.

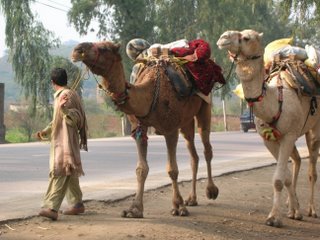

Camels are one of the most exotic forms of travel. Long lines of these sure-footed dromedaries amble determinedly in and out of traffic to northern areas of Pakistan on the main highways. I wasn’t expecting to see them here and am charmed by their obliviousness to motorized traffic. They really are the lords of the road and were formerly one of the mainstays of the Silk Route linking Pakistan to the Far East. Some of these very camels may even be enroute to China. This form of trade which may not be the quickest but there is something satisfying in that it has endured for eons.

On village roads one is much more likely to come across water buffalo pulling along farm implements or loads of vegetables. Water buffalo also turn up on the main road carting gravel to and from building sites or moving furniture around town.

The animals can on occasion be truculent and the drivers impatient but one’s outstanding impression is of a general tolerance for the many beasts on the road.

Labels: Pakistan