Responding to the Pakistani Earthquake

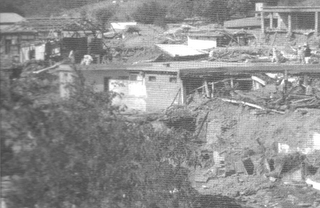

On October 8, 2005 a devastating earthquake hit northern Pakistan killing tens of thousands and injuring an even greater number. International and Pakistani relief and rescue operations were mounted. The affected area was remote and difficult to reach. Many days passed before rescue workers had dug out all those pinned under building debris.

Such catastrophic events often result in an outpouring of aid, but such assistance, in the developing world, is rarely adequate to meet all needs. Much of what needs to be done, falls to local people who have few resources. Yet they have great resiliency.

Frontier Primary Health Care (FPHC)is a small NGO struggling to make ends meet in North Western Frontier province. They work in communities located not far from the area affected by the quake, felt the shock and aftershocks, heard about the quake and sprang into action. Staff and volunteers collected clothes, bedding, shoes and food items from the villagers in their area. Dais, the local trained midwives present in all FPHC villages and camps, went from home to home in their own areas to gather donations. Some people actually gave the clothing and footwear they were wearing at the time. A widow contributed clothes recently purchased for her children to celebrate the end of Ramadan. Health units and clinics packed up as many bandages and medicine as they could spare.

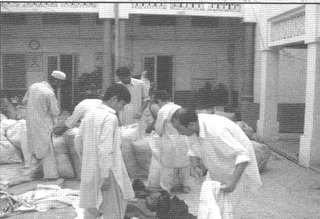

With winter coming on, it became clear, that the people who had been displaced needed blankets, quilts and mattresses, so staff members collected old clothes and linens and had them converted into blankets in local cotton mills. Within a few days, by mobilizing and informing the people in their area, Frontier PHC staff had collected massive mounds of supplied. Staff set to organizing and packing the all the material. More than eight vans and trucks were filled the donated supplies and driven to the affected area. They were among the first local groups to arrive at the scene of the quakes.

With winter coming on, it became clear, that the people who had been displaced needed blankets, quilts and mattresses, so staff members collected old clothes and linens and had them converted into blankets in local cotton mills. Within a few days, by mobilizing and informing the people in their area, Frontier PHC staff had collected massive mounds of supplied. Staff set to organizing and packing the all the material. More than eight vans and trucks were filled the donated supplies and driven to the affected area. They were among the first local groups to arrive at the scene of the quakes.Their arrival in the Batagram area was greeted enthusiastically. The donated articles were greatly appreciated and put to immediate use. Teams from UNICEF and the Ministry of Health were already on site. Using quick upper arm survey, they had determined that malnutrition was a major problem among the children under five. This is something that was likely to be quickly exacerbated during the post quake period, causing high death rates in children. The problem was that not only had the quake destroyed homes but crops and stored food supplies had been lost, as well as cooking utensils, making it difficult for families to prepare food for already compromised children.

Consultations were held with Frontier Primary Health Care on the spot. With their extensive experience in nutritional rehabilitation and establishment of demonstration kitchens, FPHC was requested by the UNI

CEF and Ministry of Health officials to assist in establishing nutritional rehabilitation in several of the affected areas.

CEF and Ministry of Health officials to assist in establishing nutritional rehabilitation in several of the affected areas.In the meantime, friends of FPHC, especially a former FPHC administrator from Scotland, had been successful in raising funds from groups such as Quakers, Scottish Executives and the Cadbury Trust in UK. These funds were used for purchasing equipment for the demonstrations kitchens and stoves for dislocated families to enable them to prepare food for their children. Quantities of edible food items such as rice, beans, lentils, oil and sugar were provided to enable the nutritional rehabilitation program to continue over the winter.

Three of FPHC’s Master Trainers were loaned to quake-affected regions of Shangla and Batagram districts. They set up a curriculum and timetable for training staff in running a nutritional rehab program. In collaboration with locals, they identified appropriate sites for demonstration kitchens in the camps and quake-affected areas. This initial planning was followed by training workshops for the health workers. Preparation of supplementary foods for malnourished children, implementation of nutritional monitoring and operation of demonstration kitchens were covered in the training programs.

FPHC staff has never been formally trained to respond to humanitarian crises. They don’t have an emergency response plan for their health units or for their organization. Their own facilities are strapped for medical supplies, frequently running out before month end. They are never sure if they will be able to pay staff salaries for more than a year ahead. Compared to health organizations in North America they are woefully unprepared for a disaster of this magnitude.

What they do have is a large and compassionate heart for their fellow humans, a vision of how a health organization needs to operate and the skills and experience that come from operating within the ever present constraints of scarce resources. It seems to be more than enough. Indeed, they are constantly demonstrating what is possible with very little at all.

There is a development exercise used with people interested in international work. In a group, people are asked to write down one word for the first image that comes to them when they think of a developing country such as Pakistan. Then they are asked to say the word. The words are all written on poster paper. When they have responded, the resource people, who have worked or lived in the country, give their word. Almost without exception, those who have not been to the country come up with negative, dark and depressing words while the resource people provide positive, hopeful and happy images.

I think our negative images of poorer countries come from applying the facts we know about the country to our own lives. For example, in Pakistan the Gross National Income is $410 per annum, 38% of under-fives are moderately or severely malnourished and 19% of newborns are underweight, suggesting malnutrition of their mothers. (UNICEF 2002 data) . Such figures argue for the existence of a humanitarian crisis even before any earthquake arrives to add injury to insult.

But while such numbers are real and represent an oppressive material poverty, they fail to capture the social cohesion that exists, the cultural richness that abounds and the vitality and strength of the people.

For an epidemiologist, numbers are important. The response of FPHC staff, volunteers and community to the earthquake like the statistics that describe Pakistanis’ health are however, better reflected in the following quote.

Everything that counts can not be counted.

Everything that can be counted, may not count. ---Chas Garfield

Photos: from FPHC Annual Report,2005

Labels: Pakistan

3 Comments:

Excellent post! I can see that I have a lot of catching up to do!

Am just now starting to catch up on weeks of being "over my head" busy ... don't give up on me! :o)

What an excellent piece, BB! You do a very important job of humanizing and keeping us mindful of the larger world picture, and you do it well. Thank you for that contribution.

You will be submitting this to Grand Rounds, right?

Moof and TundraPa--

You are too sweet, my loyal readers you!

Post a Comment

<< Home